The Climate Movement Must Be Dynamic Enough

Olympian Fields of Action Series: Post #8

By dynamic enough, our fourth characteristic, imperative, and Movement-building goal, I mean moving forward with a healthy, pragmatic relationship between:

the tried-and-true;

discipline;

freedom, and;

creativity.

Thus, to be dynamic enough is to combine and balance the tried-and-true and discipline with two of our Movement Values — freedom, and creativity. As we bring about this dynamic combination we must employ another of our movement values: pragmatism.

It is the dynamic tension between these, brought together with our passion and what makes us deep enough, that will propel us forward in making the impossible possible and the possible actual and the actual beautiful as we make our future come faster.

Tried-and-True: As Climate Movement Member-Athletes we have a great deal to learn from those who have run the race before us to create a better world. For example, we must not be so arrogant that we feel we have nothing to learn from the wisdom of movements from the past, such as the US civil rights movement. We must let past movements and their practitioners “coach” us.

Discipline: Any great athlete also knows that raw talent only goes so far. Guided by their coach, they must have the discipline to put in the training to improve their form and understand how best to perform, pace themselves, and know when to make their move to achieve victory. We must combine talent and discipline to get the most out of both.

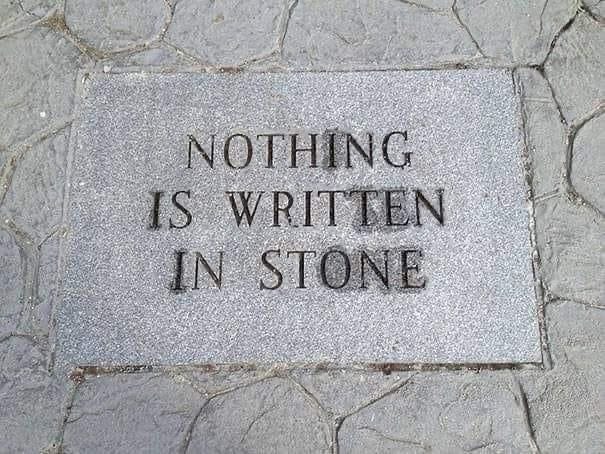

Discipline can be conflated with the tried-and-true, or, worse, with “the way we’ve always done things.”

Discipline and rigidity are not the same thing. Discipline serves purpose. It is a key factor in achieving goals. It can take discipline to change the way we do things to better achieve our vision.

Part of the discipline of Climate Movement Athletes is to remain committed to overcoming climate change by creating a just and prosperous sustainability that enhances wellbeing for everyone and everything. That’s why our Climate Movement Promise includes that we will have a “sustained commitment to collective action over time,” and why our seventh characteristic/imperative/goal is for our Movement to exist “long enough” to achieve our vision, purpose, and Major Goal.

We must also be disciplined in living out our Movement Values, such as nonviolence, as we continually press forward and are active enough to make our future come faster. It is our discipline, grounded in our love, that will make us active enough.

Freedom: Without freedom, the past and discipline can be prisons. Without freedom, we will never become big and broad and active enough, passionate enough, deep enough, or creative enough to fulfill our destiny, because freedom is at the heart of our movement. We must have the freedom to say yes or no. Only then will we have the passion and depth to stay the course, to put in the training, to run the race set before us. Our ability to say no, to quit, pushes us to dig down deep within ourselves and rely on others as they encourage us along the journey, as we continue to say yes all the way to victory. Every step we can say no; every step we must accept the support of others and find it within ourselves to keep on saying yes.

We must have the freedom to keep going, the freedom to strive towards the fullness of freedom.

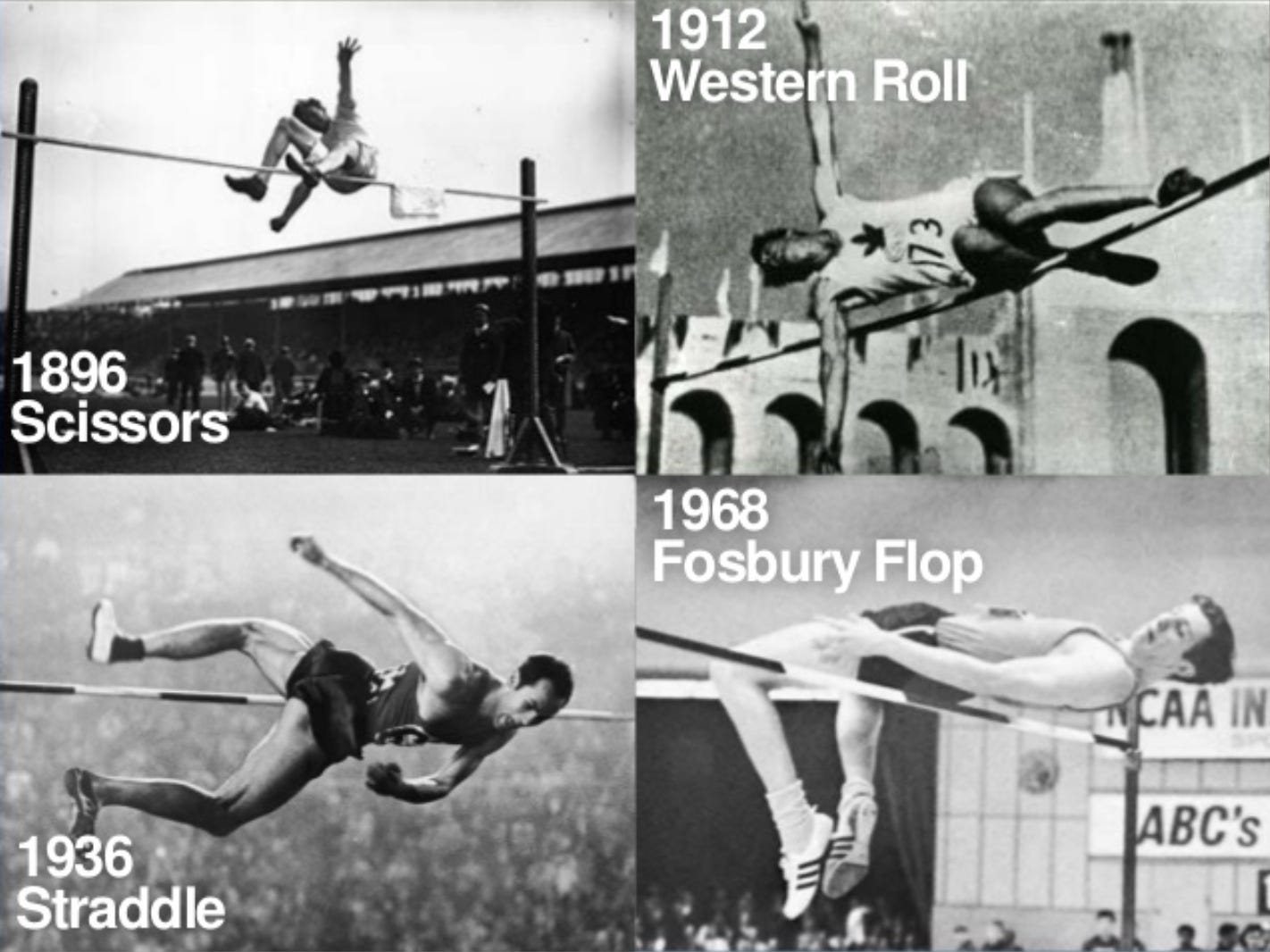

Creativity: We also must have the freedom to chart our own course: to create a new way to compete, or to choose another path, or, if need be, create a new path — or even a new sport.

One of the greatest innovations in sports history was showcased at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. There an unknown high jumper named Dick Fosbury won the Gold Medal by using a completely new and dramatically different technique that came to be known as the Fosbury Flop. He literally did things backwards.

However, this new approach wouldn’t have been possible without the introduction not long before of a new technology: the deep foam crash pad or “Port-a-Pit,” invented by a physical education teacher and track-and-field coach, Donald Wallace Gordon.1

Earlier high jumping techniques were developed to get one over the bar and land without causing serious injury. The landing surface was hard ground, or ground covered in saw dust, sand, or low mats. Fosbury’s high school in Oregon was one of the first to have Gordon’s deep foam Port-a-Pit. But coaches and athletes were not thinking of how this could alter one’s technique.

Fosbury’s efforts in sports grew out of grief and tragedy.2 When he was 14 he and his 10 year old brother were biking home when his brother was hit by a drunk driver and killed. This devastated his parents’ marriage and they divorced a year later. Fosbury needed an outlet for his grief and guilt and tried out for but didn’t make the basketball and football teams. Eventually he made the track team in the high jump.

In coming up with his new method, Fosbury was simply trying to get over the bar. He had been the worst high jumper at his high school and was afraid of getting cut from the team, losing his outlet for his grief in the process. During a competition in his sophomore year in 1962, wanting to stay on the team, and score points and help his team, and having failed to do so with the methods he had been taught, through instinct and intuition Fosbury invented his new approach on the spot and cleared the bar. Thereafter, Fosbury’s coach made him practice the standard style then employed, the Straddle, but allowed him the option to do his new approach in competitions.

In Fosbury’s new approach, he jumped off “the wrong foot” and attempted to go over the bar “backwards.” This allowed his center of gravity to actually stay below the bar, even as he arched his back and kicked his legs over the bar. Initially he was ridiculed for this unorthodox approach. But he ignored such scorn because it was no match for the emotional payoff from victory, which helped keep grief and guilt at bay and lead to Gold.

This innovative technique, born out of grief and desperation, withstanding ridicule, an organic and strategic change combo arising out of necessity, was made possible by Gordon’s new technology (an example of ARTC in sports). When the tried-and-true didn’t work for him, Fosbury was driven to create a new way. And every Olympic Gold Medal winner in the high jump ever since has done so using the Fosbury Flop.

While it is right and good to honor the past and live out its wisdom through discipline, we must also let our value of pragmatism have us open to change if a new way works better.

In sum, whatever works and makes us better as we become the greatest and most long-lasting social change movement in the history of the world, that’s what we should do. If tried-and-true makes us better, that’s what we should do. If the tried-and-true isn’t working for us, like Dick Fosbury we should have the discipline to come up with something that works better, even if it means the wrong foot backwards.

Whatever works best — the tried-and-true or something new — because the chronos-kairos-climate-clock demands it.

When freedom and creativity are ascendant, we have what I call organic change (see next posts). This is curvy, non-linear, messy change.

So these four — the tried-and-true, discipline, freedom, and creativity — must be held in a dynamic tension that propels us forward, where our Movement Values of wisdom and pragmatism join together to make us bigger, better, and faster. We must lean forward into the future, guided judiciously by the past even as we are ever open to a better way to make our future come faster.

We must be organic, but rooted. Anchored, but nimble. Adaptable, but grounded. Evergreen, but always Spring. New, and tried-and-true. Wise and pragmatic.

Together, we must be them all. We must be dynamic enough. Join us!

If you are new here, check out our Intro Series, and the earlier posts in this Olympian Fields of Action Series. If you like this post, please “like,” comment, and share. And thanks for all you’re doing.

See Eric S. Hintz, “The Fosbury Flop — A Game-Changing Technique,”(April 8, 2021): https://invention.si.edu/fosbury-flop-game-changing-technique.