Early Action Against Pollution in the United States — Climate Movement Forebearers

Our Story Together Subseries Post #1.2

While the past created our problem, it has also provided us with those who have gone before us who strove on their own Olympian Fields of Action.

With the Industrial Revolution ordinary people became rich and escaped the Malthusian Trap.

But enjoying that same quality of life meant that some became dissatisfied with the impact industrial pollution had on their wellbeing. Quality of life also meant health and a beautiful environment not marred by pollution.

Starting in the latter part of the 19th Century voices of opposition to fossil pollution began to emerge in what were then called “anti-smoke” campaigns. They were known as such because industrialization’s pollution was then called smoke, which bellowed from smoke-stacks. These anti-smoke/pollution activists were primarily middle-class white women reformers who saw industrial smoke as a dirty threat to their family’s health and thus a legitimate part of their concern. They began to push local governments to clean up their skies. Industrial smoke was considered a local issue, not a national one. Building taller smokestacks, so that local pollution was less obvious in its impacts, became a key tactic.

There were three basic categories of actors in these early efforts to do something:

pro-action types — regular folk activists and supporters of action;

experts, in this case engineers and scientists, and;

government-affiliated decision-makers — politicians, judges, and bureaucrats.

The activists pushed and made it an issue with supporters backing them up. But as reformers with many other problems on their plates and no organization focused on the environment to help stay the course (since they didn’t yet exist), their attention could be short.

The experts — many with connections to the industries themselves — offered theories and proposed technical solutions.

Politicians and bureaucrats sought solutions that did something, but nothing too onerous, usually in cozy dialogue with industry leaders and their engineers and scientists. Education, greater efficiency, and the belief in technological progress were the proposed answers.

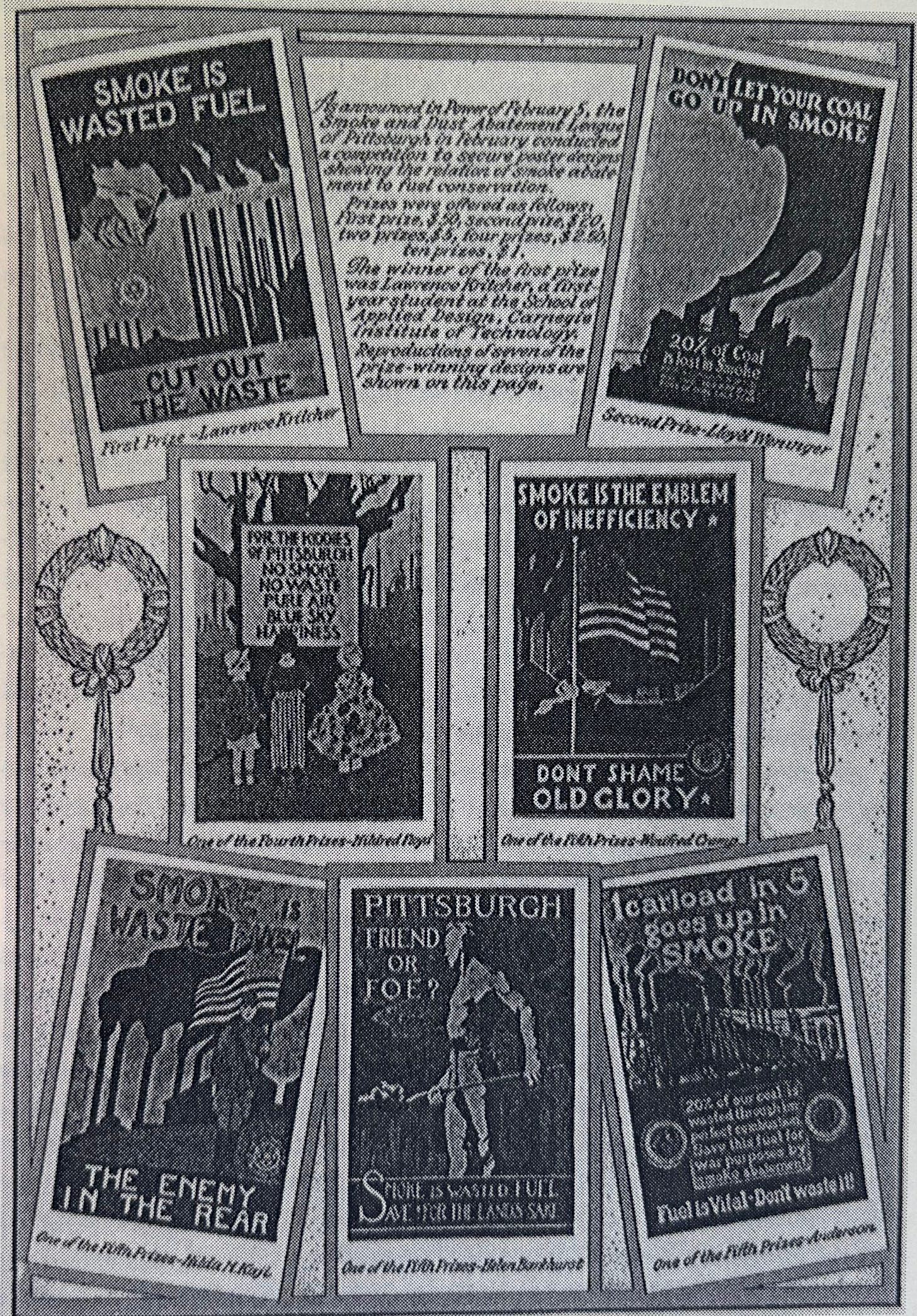

Pollution reduction, or “smoke abatement” as it was called, was modest at best. The reformers were well intentioned, but their efforts lacked staying power. Most large cities created smoke abatement bureaus, but their jurisdiction was constrained by city limits — and, of course, pollution cares not about human-drawn boundaries and jurisdictions. In many cases the bureaus were run by mechanical engineers with expertise in coal burning technologies and who were very close to the polluting industries. They preferred persuasion and voluntary efforts rather than pollution reduction requirements. They focused on how to burn coal more efficiently, and not on switching to a cleaner way to create useful energy.

Despite their limited achievements, the anti-smoke campaigns and the smoke abatement bureaus in the latter part of the 19th Century and the early part of the 20th demonstrated that the pollution-equals-progress equation no longer worked for many. “As Harper’s Weekly noted in 1907, no longer was a visibly active stack a ‘badge of great prosperity.’ Perception had changed, as many urbanites looked upon the dark clouds and saw no progress, only pollution.”1

Over a century later the three basic categories of actors remain the same: pro-action types, experts, and government-related decision-makers. Since then environmental groups have been established, scientists not associated with industry have come to the fore, and major laws and regulations have been passed and implemented. But with climate change the problems of jurisdiction and pollution not respecting political boundaries are even harder problems to solve.

That’s why, all over the world, the Climate Movement must become the greatest and most long-lasting social change movement in the history of the world, 400 million strong by 2030. Join us!

If you are new here, check out our Intro Series, as well as other posts in this Our Story Together Series. If you like this post, please “like,” comment, and share. And thanks for all you’re doing.

As quoted in David Stradling, Smokestacks and Progressives: Environmentalists, Engineers and Air Quality in America, 1881-1951 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999): p. 77.