Climate Change and The Who of Justice: Rich and Poor Countries

Hope and Justice Series Post 2.2

While various terms have been used, — “developed,” “developing,” “least developed,” “Annex I” and “Annex II” — this comparison between rich and poor countries has been at the heart of the international climate negotiations from the very beginning.1

The first climate change treaty — from which all subsequent negotiations and agreements have followed — was negotiated in Rio at the Earth Summit in 1992. Currently all 198 countries recognized by the United Nations (UN) have ratified this treaty, called the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It sums things up nicely in Article 3.1. All countries or “Parties” of the treaty:

should protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations of humankind, on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. Accordingly, the developed country Parties should take the lead in combating climate change and the adverse effects thereof.

Things to note.

Both present and future generations are recognized.

Equity — though, crucially, not defined — should determine the appropriate level of contributions by nations.

The word “equity” is modified by the phrase “in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” (amazingly abbreviated as CBDRRC by some). Subsequently called a principle, this phrase has become a mainstay of international negotiations.

As the next sentence makes clear in saying that developed countries should take the lead, the CBDRRC principle recognizes that (1) historically, rich countries bear more responsibility for climate change, and (2) poor countries have fewer resources to address the problem.

The “J-word,” justice, does not appear, and rich countries, especially the US, worked hard thereafter to keep that word out of official documents of the climate negotiations. That’s because in international law “justice” can connote wrongdoing, guilt, moral culpability, and liability that requires retribution and/or restitution/reparations. (The words “‘climate justice’” finally appear in quotation marks in the preamble to the Paris Agreement with so many qualifiers as to render it absolutely toothless.)

The key turning point in the international negotiations process begun by the Rio Climate Treaty, aka the UNFCCC, was the 2015 meeting ten years ago in Paris — also known as “COP 21,” as it was the twenty-first meeting or “Conference” of the nations or “Parties” who have ratified the UNFCCC.

Article 2 of the Paris Agreement describes its purpose. Unlike Article 3 in the UNFCCC just discussed, here there is no differentiation between nations when it comes to whether or not countries will reduce emissions. All countries — rich and poor and all those in between — are being asked to do so. Nevertheless, such efforts by all nations must be done:

“in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty”;

by “pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels”;

in keeping with “low greenhouse gas emissions development” and “climate-resilient development,” and;

reflecting “equity” and “the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in light of different national circumstances.”

by “increasing the ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change and foster climate resilience and low greenhouse gas emissions development in a manner that does not threaten food production.”

Even though loathe to use the “J-word,” the Paris Agreement also strives for justice. Climate change must be overcome — stop bad stuff — while simultaneously eradicating poverty and creating prosperous sustainability — set wrong right and make things better.

In keeping with this, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) Special Report on 1.5C, which was commissioned by the Paris Agreement, was done “in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty.”2

They note that:

“limiting global warming to 1.5°C, compared with 2°C, could reduce the number of people both exposed to climate-related risks and susceptible to poverty by up to several hundred million by 2050.”3

Every tenth of a degree matters, a prophetic mantra uttered by many scientific experts today.

But how we limit warming matters. The Catalytic-4 must work for justice: stop bad stuff, set wrong right, make things better. In overcoming the bad, we must be intentional about creating the good on all of our Olympian Fields of Action, i.e., a just and prosperous sustainability that enhances wellbeing for everyone and everything. To its credit, the IPCC’s 1.5C report, utilizing the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, kicked this discussion into higher gear by describing how some approaches would be better than others.

“Rich” and “poor” countries are not monolithic blocks, of course, and in the international context there are further differentiations among so-called developing countries. Labeling a country as rich or developed is much simpler than how to categorize everyone else.

Take China and India, for example, two indespinsable nations for overcoming climate change, given that today China is by far the world’s largest emitter, and India is the third largest (with the US in between the two). China alone contributes 35% of global CO2.4 India is projected to overtake the US in 2035.

Over the last 40 years China has eradicated extreme poverty. It has the world’s second largest economy based on GDP, and may even surpass the US to become the world’s largest in the coming decade. Around 2015 it already surpassed the US to become #1 in terms of Purchase Power Parity, (a metric that compares prices of goods in one country to another utilizing the same currency, usually dollars). Using the World Bank’s classification, in 2000 China went from a low-income to a lower-middle income economy, then a decade later to an upper-middle-income one, and now approaches the final category, a high-income status. Along the way it became an innagural member of the G20; the world’s largest emitter of climate pollution starting in 2006, and; currently contributes a whopping 24% of the world’s greenhouse gases, ranking third in emissions per person.

So is China a “developing” country, as the nation is still classified in international climate negotiations? The answer is yes according to the UN, which uses their Human Development Index (HDI) to classify countries as Very High, High, Medium, and Low. A perfect HDI score is 1.0. Countries at 0.8 or above are in the Very High category and are considered “developed.” Everyone else is still “developing.” China, currently ranked 75th in the world, is in the High category with a HDI score of 0.788.

So how many poor people does China have? Given China’s current upper-middle-income classification by the World Bank, for which the updated poverty line is $6.85 per day , 348 million people as of 2019 were poor, 25% of the population.5

So is China a rich country or a poor one? According to Forbes, they have the second-most number of billionaires in the world, behind the US. They also have the most Fortune Global 500 companies, beating the US (EMR Rpt 2021, p. 8). But based on the $6.85 per day standard they have lots of poor people, 348 million — more than the entire population of the US.

What about India, who has now surpassed China as the world’s most populous country, and has passed Great Britain as the fifth largest economy? Their HDI score is 0.644, ranking them 134th in the world. According to the World Bank they are a low-middle income country, the second-lowest classification, whose poverty line has been updated to $3.65 a day (up from $3.20 a day). Here are how many are in the various levels of poverty:6

136.8 million in extreme poverty at the updated $2.15 a day, the most of any nation;

611.9 million, 45% of the population, using the updated low-middle standard of $3.65, and;

over 1 billion, or 84% of the population, using the updated upper-middle standard of $6.85.

By whatever measure you use, India has the most poor people of any nation. Using the $3.65 and $6.85 standards, India’s poor dwarf the population of the US. And the numbers continue to grow. In 2024 using the $6.85 standard there are more poor people than in 1990, driven by population growth.7

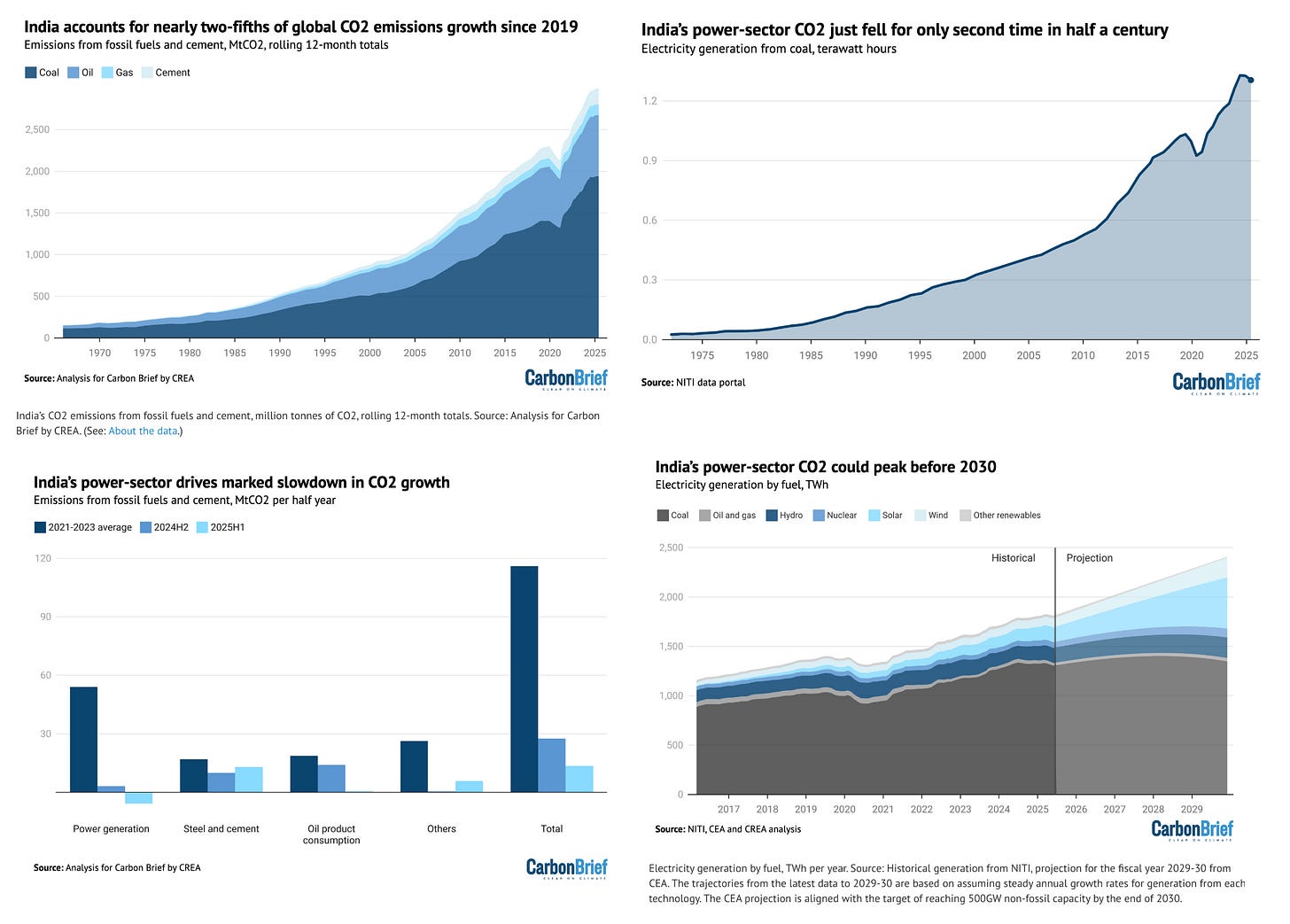

Yet India is also a part of the G20, has the world’s 5th largest economy based on GDP, is ranked 3rd behind China and the US in terms of Purchase Power Parity, and is the third largest emitter of climate pollution, contributing 6.76%. Their emissions have grown significantly over the last several decades, with coal producing the vast majority of their electricity during this time.

While India definitely has the most poor people of any country by far, it will continue to be a major, growing contributor to climate pollution. Since 2019 they have been responsible for two-fifths.

The fact is we simply cannot overcome climate change without India; but they need a great deal of economic growth to lift over a billion people out of poverty using the $6.85 standard. If the vast majority of this future growth isn’t climate-friendly, it will be much more difficult to overcome climate change.

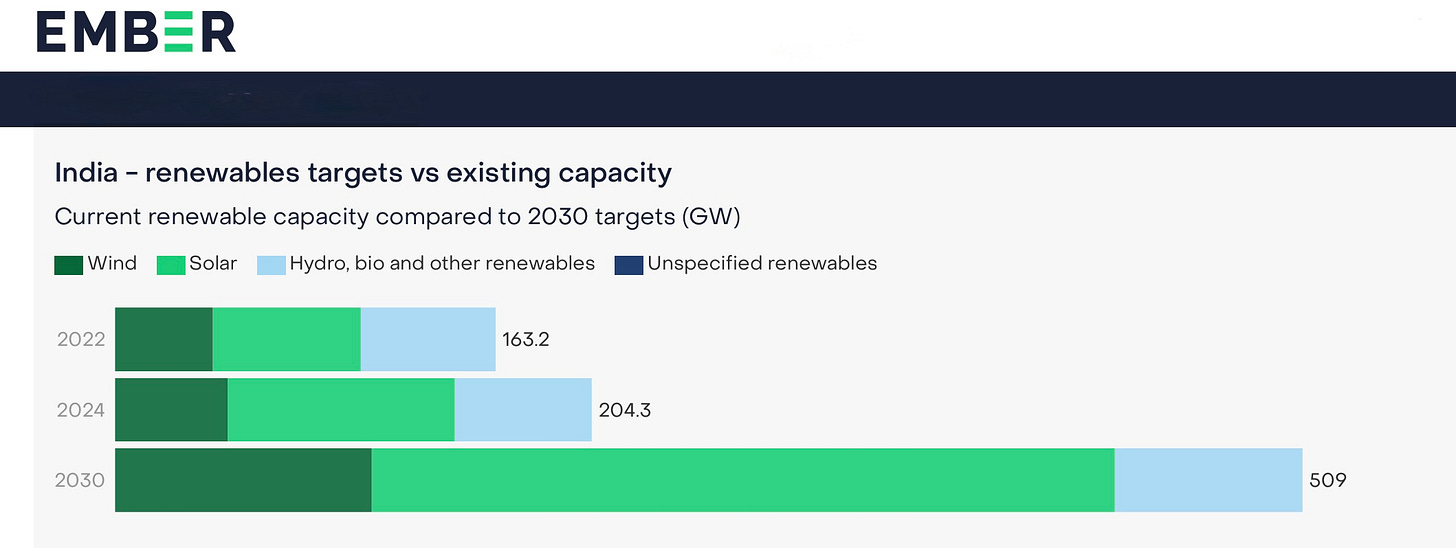

Thankfully, things are moving in the right direction. India has pledged to triple its renewable capacity by 2030. As Ember reports:

By October 2024, the country had achieved 200 GW of installed renewables capacity en route to its 2030 goal of 500 GW. Ember analysis suggests that the country would reach 42% renewable electricity generation by 2030 under current plans.

India’s clean energy production this year is up by 20%, while coal’s contribution continues to fall. As Ember reports, “In 2024, Coal generation met 64% of India’s electricity demand growth, a sharp drop from 91% in 2023.” And this year electricity from coal actually dropped. The CarbonBrief graphs below tell the story. India’s electricity sector CO2 could peak before 2030.

Globally the very good news is that the world has arrived at a place where overcoming climate change via clean energy can and does lead to poverty eradication. That’s because clean energy is now cheaper than dirty energy on price alone, not even taking into consideration the health, environmental, and climate costs of dirty energy.

In 2023, 81% of new renewable capacity produced cheaper electricity than dirty alternatives according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). In 2024 the percentage of cheaper renewables compared to dirty was even greater — 96%. That’s because solar was 53% and onshore wind was 41% cheaper.

However, price alone will not lead to a just and prosperous sustainability that enhances wellbeing for everyone and everything as called for by our vision, purpose, and Major Goal. Sub-Saharan Africa lags far behind in new clean energy.

Trickle-down justice is a mirage. To stop bad stuff, set wrong right, and make things better we must not rely only on price, but actively push for the benefits of clean energy, the power source of prosperous sustainability, to be available to everyone, especially the poor. That’s why the Climate Movement must become the greatest and most long-lasting social change movement in the history of the world. We are making hope happen. Join us!

If you are new here, check out our Intro Series, and other posts in this Hope & Justice Series. If you like this post, please “like,” comment, and share. And thanks for all you’re doing.

As I said in a footnote in my previous post in this Subseries, I use “rich and poor” when discussing justice precisely because we are talking about situations where some have too much and more than their fair share of opportunities while others don’t, and some are powerless and less powerful and marginalized and vulnerable because they lack financial resources. Others use different terms to describe these groups. When talking about nations some use the terms “developed” and “developing.” I’ve never been crazy about these labels because they can connote maturity/immaturity and superiority/inferiority. As such, I personally avoid “developed” and “developing,” as well as the word “development.”

IPCC Special Report 1.5C, Summary for Policymakers, p. 4.

IPCC SR 1.5 SPM B.5.1, p. 9.

IEA, CO2 Emissions in 2023, p. 20.

WB, Poverty & Equity, China, Apr 2023.

WB, Poverty & Equity, 2022

WB, Poverty, Prosperity, and Planet, 2024, p. 65.