Climate Change and the Poor: Who’s The Who of Justice Subseries

Hope and Justice Series Post #2.1

This is the second post in our Subseries on Who’s The Who of Justice, focused on (1) who needs justice, and (2) who is accountable for injustice.

One of the most important groups needing justice is the poor. So, who do we mean by “the poor”? That’s the focus here.

As our vision, purpose, and Major Goal proclaims, overcoming climate change must be done in a way that creates a just and prosperous sustainability that enhances wellbeing for everyone and everything. For this to be just, every person on the planet — especially the poor — must benefit from the solutions to climate change.

As we work to have the Catalytic-4 create strategic synergies, we want climate solutions to help eradicate poverty and create wellbeing for everyone. We want prosperous sustainability especially for the poor. We don’t want the poor to suffer from the health consequences of old, dirty tech hand-me-downs, chained to expensive foreign fossil sources, or local ones extracted by big oil and coal that keep the profits and leave the mess, while the rich benefit from the newer, cleaner, better ways of creating energy locally from tech they own. We want the poor to have clean, local renewable power they own, operate and maintain, and we oppose coal- and petro-colonialism.

We have our work cut out for us. For example, 685 million still don’t have electricity, including 496 million in the poorest countries.1 To rectify this, let’s achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) #7 by 2030: “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all.” But lets do so with an emphasis on sustainability as found in SDG 7.2: “increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix” by 2030.2

Let’s take the greatest threat to humanity in our time and overcome it via Catalytic-4 synergies in a way that lifts people out of poverty and into wellbeing. Let’s get rid of the bad stuff while everyone enjoys the good stuff.

Simply put: with climate solutions and through Catalytic-4 synergies we want to begin to achieve the desires and demands of justice by stopping bad stuff, setting wrong right, and making things better.

This will not happen automatically. More broadly, ARTC, the accelerating rate of technological change, could easily exacerbate the rich-poor divide and turbocharge inequality.

We cannot be gaslighted by a “trickle-down” theory of how a just and prosperous sustainability will come about. We can’t simply create the conditions whereby climate solutions can thrive and expect the poor and disenfranchised to benefit by default. We must make sure they do by working for it, fighting for it. There is no such thing as trickle-down justice.

This part of the challenge will involve efforts at every level — international, regional, national, local, communal, — and may never be fully accomplished.

While some poor countries, including the two biggest, have made remarkable progress over the last 50 years, most have remained mired in poverty.3

Climate impacts have contributed to this. One study showed that since 1961, as the earth has warmed rich countries have gotten richer but the poor have become poorer. Global warming:

decreased economic growth per person by 17-31% in the poorer countries while fossil fuels powered growth in the richer ones;

increased inequality 25% between the richest and the poorest countries, i.e., the top and bottom 10%.4

A 2024 review of relevant peer-reviewed studies found “robust evidence that climate change impacts indeed increase economic inequality and disproportionately affect the poor, both globally and within countries on all continents”.5

Unfortunately, more recently, (1) the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) the Ukraine war and other armed conflicts, and (3) climate impacts, have made poverty reduction that much harder. For the first time in 25 years extreme poverty increased worldwide starting in 2019 (using the less than $1.90 a day standard). An additional 93 million were pushed into extreme poverty by the pandemic.6 There has been a rebound in some countries since to pre-pandemic levels, but not in the poorest countries, and overall extreme poverty has continued to increase. “In 2022, 712 million people (or 9 per cent of the world’s population) lived in extreme poverty, an increase of 23 million people over 2019”.7 In the poorest countries “one in four people live on less than $2.15 a day – more than eight times the extreme poverty rate in the rest of the world. One in three of these countries are now poorer on average than before the pandemic”.8 The World Bank doesn’t see this trend changing anytime soon, leading them already to call this a “lost decade” when it comes to fighting poverty.9 At least those experiencing hunger has decreased overall the last few years, a decrease of 15 million since 2023 and 22 million since 2022.10 And the number of children in extreme poverty has also decreased over the last decade by nearly 100 million.

Unfortunately, by 2030 climate change could cause over 130 million to fall into poverty.11

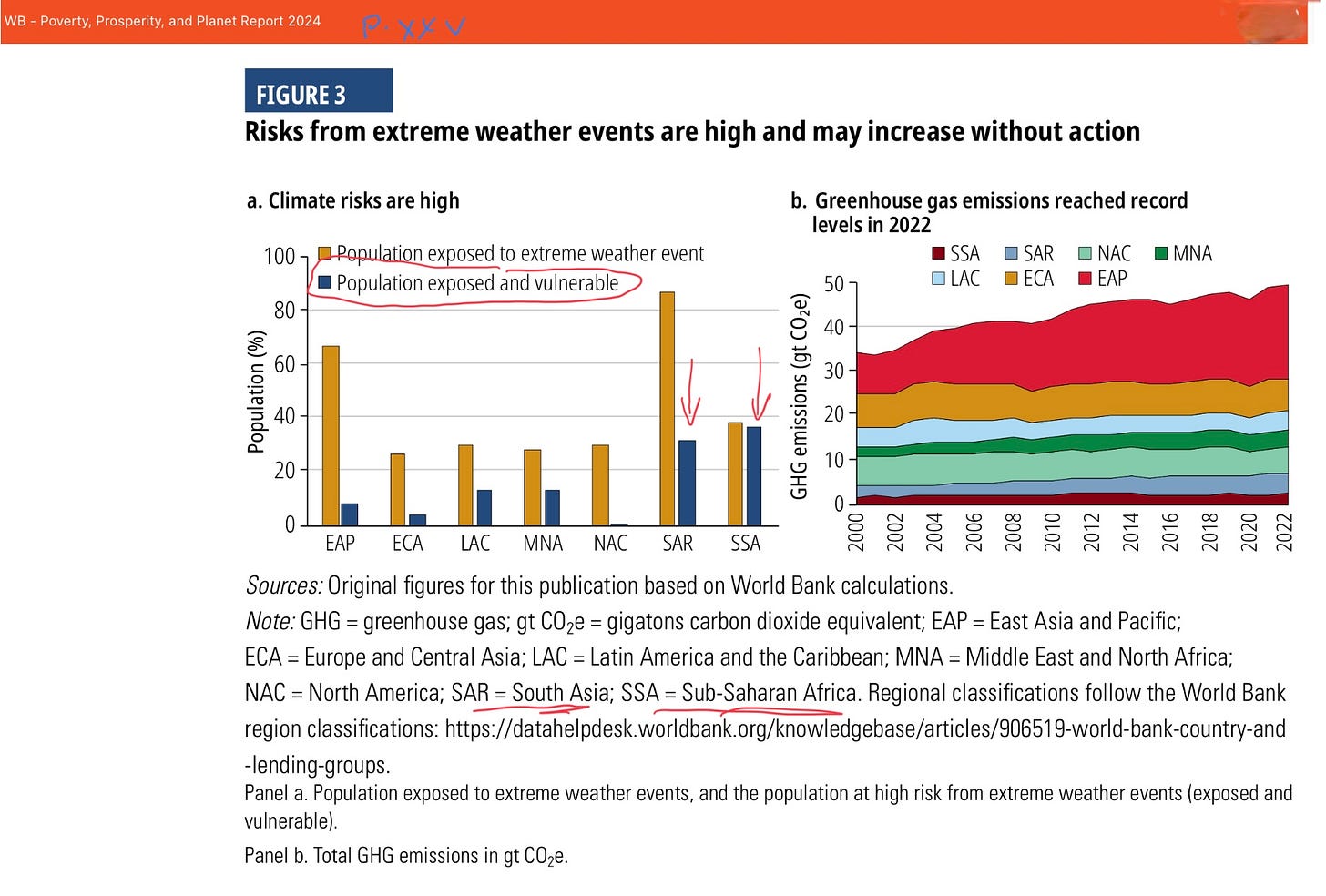

Poverty is the key factor in a person’s vulnerability to climate impacts. As Figure 3 (above) from the World Bank’s Poverty, Prosperity, and Planet report shows, Sub-Saharan Africa has the largest percentage of those both exposed and vulnerable to extreme weather events at 37.3 percent, while South Asia has the largest total population exposed and vulnerable: 594 million people (or 32% of the population).12

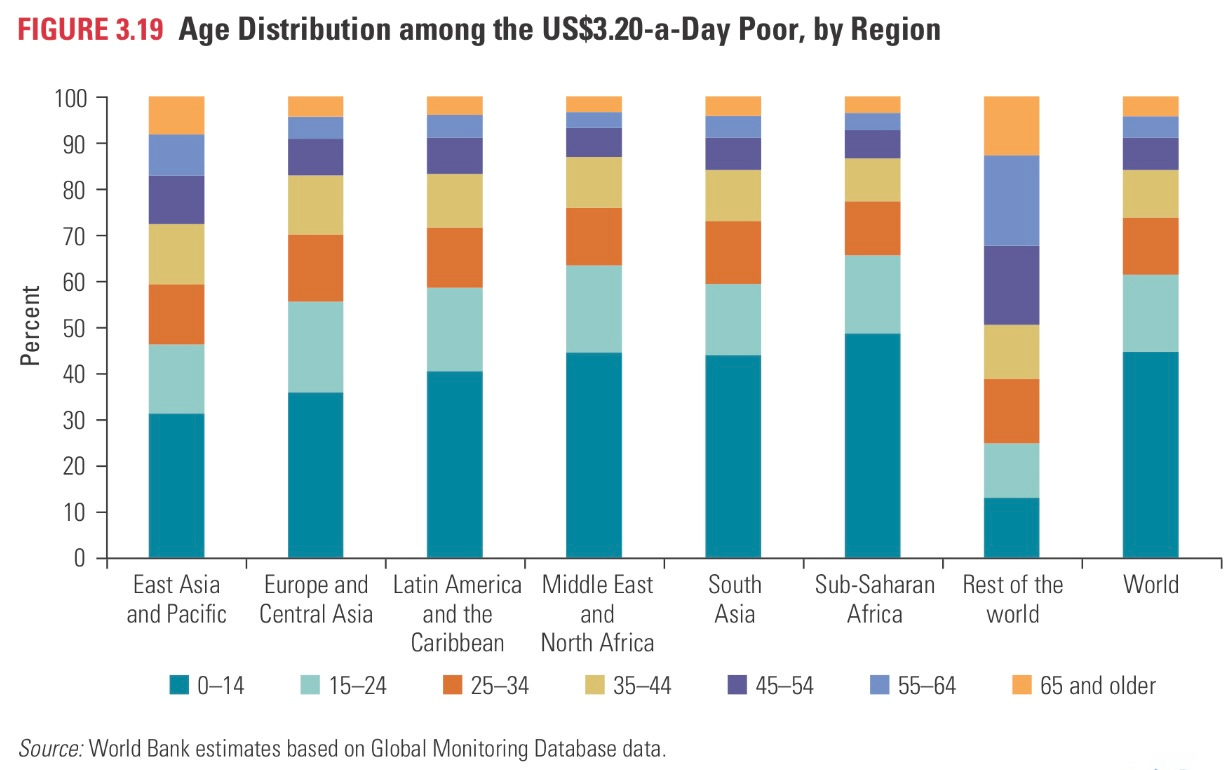

What’s more, today’s children make up half of those in extreme poverty, even though they are only one-fourth of the world’s population.13

To get a very rough sense of things, consider one climate impact. Worldwide, those who are at the risk of catastrophic flooding include:

132 million who earn less than $1.90 a day,

344 million earning $3.20 or less a day, and

588 million earning $5.50 or less a day.14

Of course, climate impacts don’t happen one at a time in isolation from all the other problems the poor have to deal with. The opposite is the case: they form a synergistic soup of death and destruction.

For example, Oxfam looked at the growth of hunger in 10 of the worst national climate hotspots created by extreme weather events. They found that:

acute hunger more than doubled from 2016 to 2021, from 21 to 48 million people;

nearly 18 million are on the verge of starvation;

these nations emit only 0.13% of the world’s carbon pollution;

all of them are in the bottom third of countries least prepared to deal with climate impacts.15

Such numbers will only grow in the future, especially if we do nothing to help them adapt and compensate them for loss and damage (part of setting wrong right), and create prosperous sustainability to enhance their resilience potential (making things better).

As I said, we have our work cut out for us. Yet every step towards justice on all of our Olympian Fields of Action creates a better, more beautiful world, and is worthy of our struggle.

Finally, when it comes to differences between rich and poor16 in the climate context, we need to recognize at least four situations (each of which will be covered in upcoming posts):

2) The poor in the poorest countries

3) The poor in emerging countries

4) The poor in rich countries.

These are illustrative, not exhaustive. Differentiating between rich and poor countries is the broadest comparison and will be covered in the next post, followed by the others in succession.

One thing these four situations have in common: no matter where or when you live, if you are poor you are more vulnerable to climate consequences even though you have done little or nothing to cause them.

Where’s the hope in all of this? Hope does not deny or ignore injustice. It does the opposite. Only by seeing reality can we work to change it. And doing so together gives us hope. Join us!

International Energy Agency (IEA) et al, Tracking SDG7, 2024, p. 11; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), LDC Report 2024, p. 39.

IEA et al., Tracking SDG7, p. 65.

UNCTAD, LDCs Rpt 2021.

Diffenbaugh and Burke, Global Warming Increased Inequality, PNAS, 2019.

Mejean et al, “Climate Change Impacts Increase Economic Inequality,” Env. Res. Let., 2024.

SDGs 2022 Rpt, p. 26.

WB, Poverty, Prosperity, Planet, 2024, p. xxiii.

World Bank, Shared Prosperity (2020), p. 1.

WB, Poverty, Prosperity, Planet, 2024, pp. xxv and 169.

WB, Shared Prosperity (2020), p. 125.

World Bank, Shared Prosperity (2020), p. 146. By the way, in September 2022 the World Bank adjusted its poverty lines from $1.90 to $2.15 for extreme poverty, from $3.20 to $3.65 for lower-middle income countries, and from $5.50 to $6.85 for upper-middle-income countries. My discussion will reflect both the older $1.90, $3.20 and $5.50 standards and the updated $2.15, $3.65, and $6.85 standards.

Oxfam, Hunger in a Heating World (2022) p. 2

A note on terminology. I use “rich and poor” when discussing justice precisely because we are talking about situations where some have too much and more than their fair share of opportunities while others don’t, and some are powerless and less powerful and marginalized and vulnerable because they lack financial resources. Others use different terms to describe these groups. When talking about nations some use the terms “developed” and “developing.” I’ve never been crazy about these labels because they can connote maturity/immaturity and superiority/inferiority. As such, I personally avoid “developed” and “developing,” as well as the word “development.”