Climate change and the Poor in Poorest and Emerging Countries

Hope and Justice Series Post #2.3, part of The Who of Justice Subseries

In our climate context, The Who of justice involves two basic categories:

those who need justice, to whom justice is due;

those who are accountable for injustice.

This post is the fourth in this Subseries that deals with those who need justice. (Click the links to see the first, second, and third posts.)

The poor are the largest group of those who need justice as it relates to climate change. This post continues the discussion of who we mean by the poor.

The Poor in the Poorest Countries

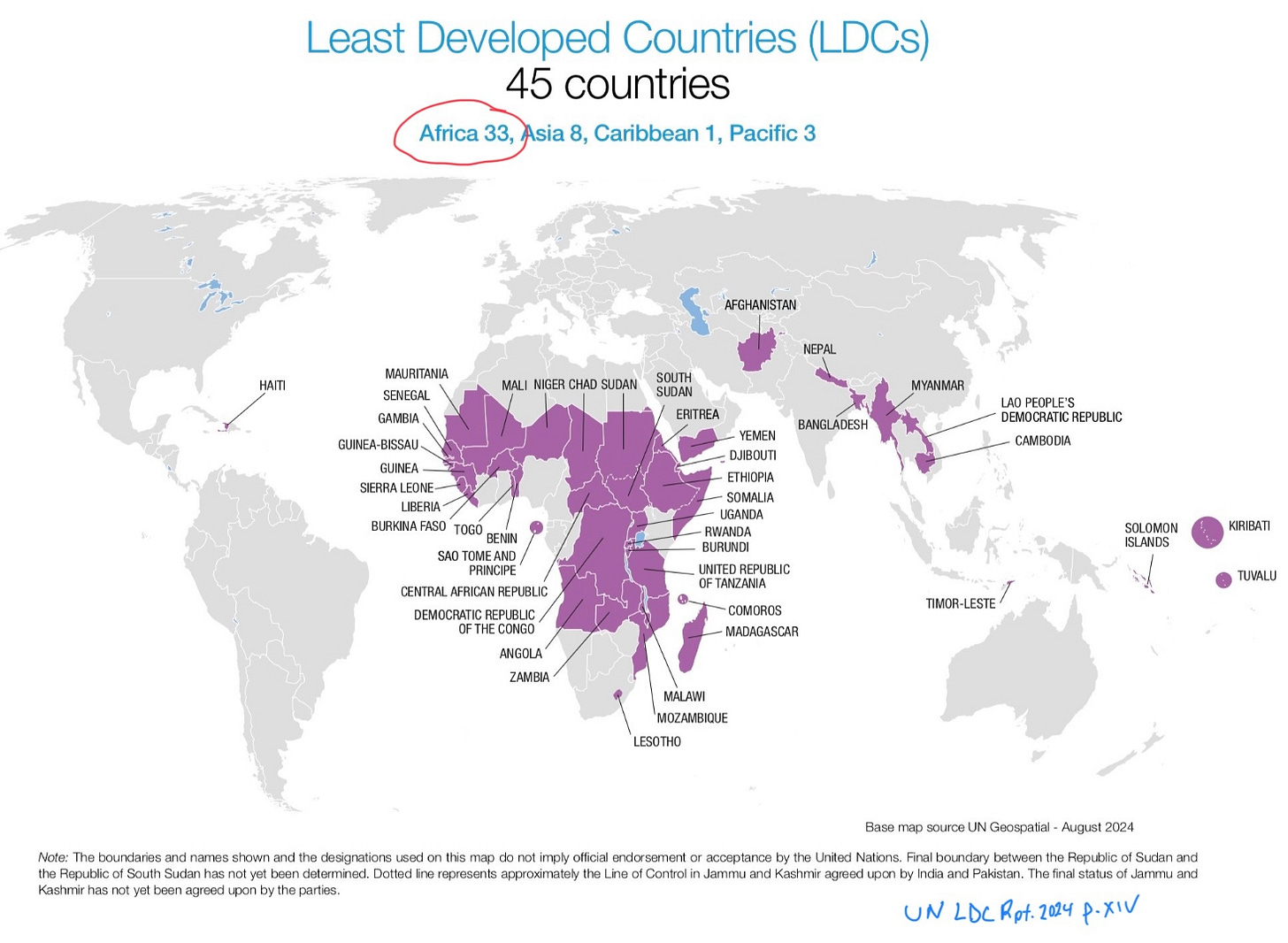

When it comes to the poorest nations, based on the United Nations (UN) classification we are talking about:

44 countries,

880 million people, and

about 12% of the world’s population.

Of the 380 million around the world living in extreme poverty, more than half live in the poorest nations — over 190 million.

In contrast to the poor in emerging and rich countries, the poorest nations have less resources to help their poorest citizens. Recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic is just the latest example. Most rich countries fully offset the pandemic’s financial impact on poverty, but the poorest countries were only able to muster a 25% offset.1

The 190 million poorest of the poorest are the most vulnerable to climate change of any group on the planet. When they try to pull themselves out of poverty, climate change helps push them back into it. Yet they have essentially done nothing to cause this deadly threat to themselves and their loved ones.

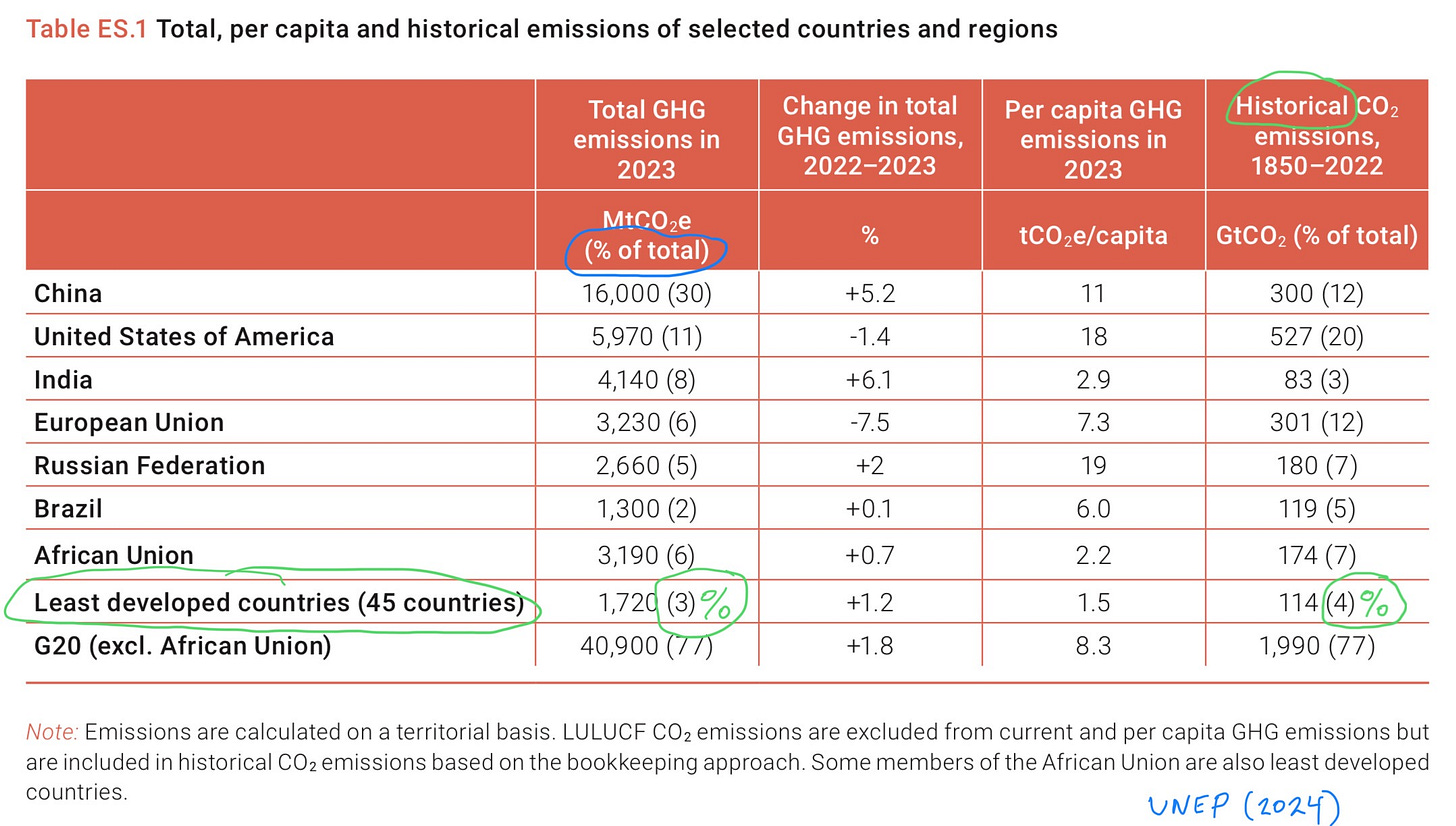

As can be seen in the graph above, the poorest countries contributed:

3% of current GHGs, and

4% since 1850.2

By contrast:

The G20 countries contribute 77% of current GHGs.3

The wealthiest top 10% of individuals around the world contribute nearly half, while the bottom 50% contribute about 10%.4

Over the last 50 years

69% of climate-related deaths have been in the poorest countries.5

Climate impacts may push

an additional 132 million from these countries into extreme poverty by 2030.6

Thirty-three of the 44 poorest countries are in sub-Saharan Africa (see map, above), which has 16% of the world’s population but 67% of those in the world living in extreme poverty.7

Taking flooding as a very rough proxy of climate risk:

170 million of those in extreme poverty ($1.90 a day), including 75 million in Sub-Saharan Africa, have significant flood risk, which climate change will make worse.8

Add in drought and increased temperature impacts on crops, health threats like increased vector-borne diseases and increased heat, forced migration from climate consequences, and destabilization of societies and governments, and you have a deadly formula making the lives of the poorest of the poor even worse.

Climate consequences for the poorest of the poor is the injustice of climate change in its most potent, brutal manifestation.

The Poor in Emerging Countries

The total population of emerging/middle countries9 is about 5.9 billion. Here are approximately how many fall below the World Bank’s poverty levels:

338.5 million below $2.15 a day

391 million below $3.65 a day

3 billion below $6.85 a day.10

So the poor in emerging countries make up close to half the world’s population. And while the two major emerging countries, China and India, as well as others, have made progress on reducing extreme poverty, climate change combined synergistically with other major problems has already contributed to a roll-back of some progress, and will continue to do so.

More than half of the world’s population are the poor living in the poorest and emerging countries.

All told, those in poverty in both the poorest and the emerging countries comprise more than half the world’s population.

But Where’s the Hope?

Where’s the hope in all of this? The hope is in seeing the challenge before us and facing it together. If we don’t see it, we won’t do anything about it. The hope is in our yearning for a just world, a world that feels right, and striving together to make hope happen by making justice happen. Hope and justice are a symbiosis in our hearts and minds. And together as we live in and live out our values we are working to make the impossible possible and the possible actual and the actual beautiful and our future come faster — especially for the poor. We are the hope we’ve been waiting for. Join us!

If you are new here, check out our Intro Series, as well as earlier posts in our Hope & Justice Series. If you like this post, please “like,” comment, and share. And thanks for all you’re doing.

World Bank, Poverty, Prosperity, Correcting Course, 2022, p. xxi.

United Nations Environment Programme, No More Hot Air (2024), p. xiii.

UNEP, No More Hot Air (2024), p. xiii.

UNEP, Emissions Gap Report 2023, p. 9.

International Institute For Environment and Development (IIED), Unjust Cost, 2019.

WB, Reversals of Fortune, (2020) p. 162

WB, Pathways out of the Polycrisis (2024).

Rentschier, et al, “Flood Exposure and Poverty in 188 Countries,” Nature Communications, June 28, 2022.

I believe the concept of emerging countries is helpful to us and is preferable to other 4-part classifications (e.g. the UN’s, the Word Bank’s) for three basic reasons. First, many people have a general if somewhat vague sense of what is meant: an emerging country is in the middle between the poorest and the richest countries, but is becoming better off. Second, it keeps our classification of nations to three, and our brains like things in threes. Third, it has a sense of forward momentum. However, there is one drawback to having emerging refer to the countries in the middle: while most are becoming better off, some are stalling or moving backwards.

Those who fall in the $2.15, $3.65, and $6.85 categories were calculated using information from the World Bank at www.data.worldbank.org.